THE

ROMANCE

IS BACK

By David Gebhard

For close to 100 years, Santa Barbara has been known for its Hispanic architecture, and in the 1920s this tradition was greatly admired in California and nationally. Later, with the embracing of Modernist architecture in the 1930s, Santa Barbara’s commitment to the Hispanic appeared to America’s architectural establishment as a regrettable, child-like error that would eventually correct itself.

To the dismay of the Modernists, however, Santa Barbara continued on its quirky course. One would assume that, with the toppling of Modernist architecture in the late 1960s, Santa Barbara would once again have been in favor with the architectural establishment–and indeed a handful of national figures, such as architects Charles Moore and Robert A. M. Stern, spoke warmly of the tradition. But on the whole the Post Modernists were still uneasy with it.

With Post Modernism in fashion, a number of Santa Barbara’s younger architects sought to maneuver the Hispanic image in their buildings so they would be read as Post Modernist. But this updated Hispanic, like the Modernists’ earlier attempts, did not on the whole work. As a group, the architects simply took over the Post Modernist vocabulary of square windows, gabled and pyramidal roofs, and stucco walls without understanding the conceptual bases of either Post Modernism or Traditionalism.

Most Santa Barbara clients in the 1970s and 1980s wanted traditional buildings. And while they were generally not as familiar with the European originals as were clients in the 1920s, the clients are certainly not to blame for the rash of poorly designed Hispanic buildings in Santa Barbara in recent years. That responsibility lies with the architects, who, in contrast to the Beaux Arts-educated designers of the 1920s, were simply not trained to design traditional buildings. Earlier architects had looked intensely at historic building along the Mediterranean and in Mexico, making sketches and measured drawings and thus forming an understanding of the proportions and important details of these buildings.

During the past few decades, architects such as Grant Pedersen Phillips Architects, Seaside Union Architects, Brian Cearnal Associates, Robert Easton and James E. Morris, to name only a few, have all fashioned Hispanic/Mediterranean buildings that have substantially contributed to Santa Barbara’s Hispanic/Mediterranean tradition. But never has that tradition been more creatively alive than today. Five Santa Barbara architects/designers whose work exemplifies that vitality are Paul Gray (of Warner and Gray), Geoffrey Holroyd, Henry Lenny, Thomas Bollay, and Michael De Rose. All of these designers have worked to revitalize the Hispanic/Mediterranean as a creative living tradition, and their designs argue strongly that the community’s central tradition is perhaps healthier than at any time since the 1920s and 1930s.

Happily, there is every reason to think, as we conclude this century and plunge into the next, that Santa Barbara’s quirky, often out-of-step architecture will remain will remain very much with us.

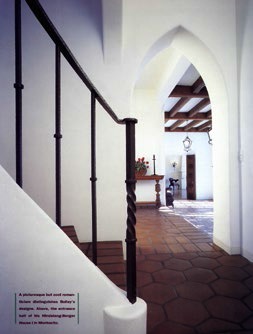

Of these designers, Thomas Bollay (Thomas Bollay Associates) comes closest to the revivalist atmosphere of the 1920s. His own house in Montecito of 1990-1992 and two Edward Hindelang-Michelle Berger houses in Montecito (Grant Castleberg Assoc., landscape architects for all three projects), capture the flavor of the earlier buildings of George Washington Smith, Reginald D. Johnson and Wallace Neff. He is especially close to Johnson’s domestic work of the 1920s with its romanticism countered by a degree of coldness and rationalism.

Of these designers, Thomas Bollay (Thomas Bollay Associates) comes closest to the revivalist atmosphere of the 1920s. His own house in Montecito of 1990-1992 and two Edward Hindelang-Michelle Berger houses in Montecito (Grant Castleberg Assoc., landscape architects for all three projects), capture the flavor of the earlier buildings of George Washington Smith, Reginald D. Johnson and Wallace Neff. He is especially close to Johnson’s domestic work of the 1920s with its romanticism countered by a degree of coldness and rationalism.

Bollay’s success is based upon a close study of the revivalist buildings, as well as their original sketches and working drawings. He has traveled to Europe, consciously trying to experience the original prototypes as the architects of the 1920s would have. His plans start with revivalist schemes but reflect current uses and how we react to indoor and outdoor spaces. His terraces generally become, almost as in Modernist designs, out-of-door living and dining spaces quite different from terraces of the ’20s. In his own house, rooms and their interconnections are picturesque- but at the same time exhibit a low-keyed, Modernist sensibility.