FOUNDING FATHER: GEORGE WASHINGTON SMITH

By David Gebhard

Late in 1929, Santa Barbara architect George Washington Smith was interviewed by the New York critic John Taylor Boyd, Jr., who was conducting a series of interviews with America’s most famous architects for the magazine Art and Decoration. The inclusion of Smith was perfectly understandable–buildings designed by this Santa Barbara architect had been, from the beginning, a favorite of the country’s leading architecture and design magazines.

New Yorkers had been exposed to his buildings through photographs and drawings in annual exhibitions of the Architectural League of New York. In a review of the 1925 League exhibition, Matlack Price wrote of Smith’s ability to realize buildings of “exquisite simplicity of design…of proportions,” together with a sensitive use of “the fine patterns of trees and shrubs made by sunlight and shadows on the walls of the house.”

Smith’s work was equally appreciated in California, where he was always mentioned as the leading exponent of the Hispanic and Mediterranean revival of the 1920s. Although her house was never built, the Hollywood film star Mary Pickford selected Smith to design a ranch house for her and husband Douglas Fairbanks Jr. “His homes, whether large or small, are remarkable in their directness,” she said in an interview in Pacific Coast Architect in 1927, “in the simplicity with which they speak the truths of this old architecture as something eminently suitable to the creation of a tradition of beauty.”

Smith’s work was equally appreciated in California, where he was always mentioned as the leading exponent of the Hispanic and Mediterranean revival of the 1920s. Although her house was never built, the Hollywood film star Mary Pickford selected Smith to design a ranch house for her and husband Douglas Fairbanks Jr. “His homes, whether large or small, are remarkable in their directness,” she said in an interview in Pacific Coast Architect in 1927, “in the simplicity with which they speak the truths of this old architecture as something eminently suitable to the creation of a tradition of beauty.”

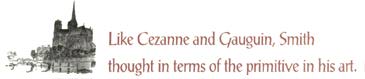

When these New Yorkers and Californians, and certainly many of his clients, characterized Smith’s designs as simple, they were responding to two important qualities: the purity of geometric abstraction in his volumes and surfaces, countered by a strong sense of the primitive. As Smith himself frequently pointed out, he thought in terms of the primitive in his own art, just as did the painters Paul Cezanne and Paul Gauguin, two 19th-century artists whom he very much admired. The impressive impact of his buildings was also an outcome of his sensitive response to each site and his high regard for landscape architecture.

His houses and other buildings throughout California, in Arizona, Texas and New York, played a fascinating visual game between strong historical reminiscences and the developing modern idiom of those years. In Europe, Smith had seen not only the wonders of Spain’s historic white cities, but also the work of many early modernists, including the Swiss/French architect Le Corbusier. “Le Corbusier,” he noted, “is a tonic. Too severe, but a pioneer with vision.”

Before he turned to architecture in Santa Barbara in 1919, Smith had experienced several divergent careers in business and in art. He was born in East Liberty, Penn., on Feb. 22, 1876, and since the day was George Washington’s birthday, he was given his name. His father was a successful and highly respected engineer, who designed bridges and elevated railroads. Smith was sent to Harvard to study architecture, but was unable to complete his formal education because of his parents’ financial reverses. He worked briefly in a Philadelphia architectural firm, but found, as he put it, that his wages did not provide him with the lifestyle he was used to. He then joined a bond firm, and was so successful that he abandoned the world of business to become a painter.

Before he turned to architecture in Santa Barbara in 1919, Smith had experienced several divergent careers in business and in art. He was born in East Liberty, Penn., on Feb. 22, 1876, and since the day was George Washington’s birthday, he was given his name. His father was a successful and highly respected engineer, who designed bridges and elevated railroads. Smith was sent to Harvard to study architecture, but was unable to complete his formal education because of his parents’ financial reverses. He worked briefly in a Philadelphia architectural firm, but found, as he put it, that his wages did not provide him with the lifestyle he was used to. He then joined a bond firm, and was so successful that he abandoned the world of business to become a painter.

He and his wife Mary Greenough went off to Paris, where they lived for three years while he studied and painted. With the advent of the First World War, he returned to the United States in 1914 and established himself in New York City, where he exhibited with William Glackens, John Sloan, George Bellows, Robert Henri and Eugene Speicher. His paintings were shown at the McDowell Club in New York, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C., and the Chicago Art Institute.

He came to California in 1915 to see his paintings exhibited at the Gallery of Fine Arts at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, and decided to stay for the duration of the war. It was Smith’s intent to return to Paris, but through Philadelphia friends he was attracted to Montecito. Since he and his wife were going to be here for a few years, he decided to design and build a studio residence. The design sources for this 1916 house were the Andalusian farm houses he had experienced on a trip to Spain in 1914.

The house was an instant success in California and nationally–it was published and republished throughout the country, and illustrations of it were used by the manufacturers of Portland Cement and by tile makers. Locally Smith “found that people were not really eager to buy my paintings, which I was laboring over, as they were to have a white-washed house like mine. So I put away the brushes and have not yet had a moment to take them up again.”

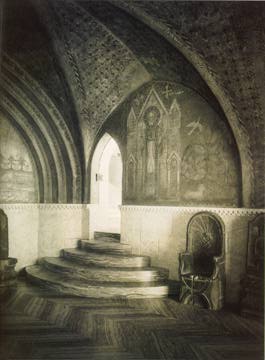

Smith’s architectural career lasted only 12 years, from 1919 to 1930. But during these years he (with the assistance of his draftsperson, Lutah Maria Riggs, who joined his office in 1922) produced a remarkable array of buildings, both in quality and quantity–of 80 designs for new or substantially remodeled homes in Santa Barbara County, 54 were built. Many were based on Spanish, Mexican and Hispanic California precedents, but he also designed in the Italian, French Norman, and English Tudor modes. His 1926-28 Crocker Fagan house at Pebble Beach is America’s one and only example of a Byzantine house. In Texas, for the Van Wyck Maverick family (1926-28), he created one of the most impressive courtyard-oriented houses built during these years, and he introduced the world of Spain to, of all places, Fisher’s Island off the coast of New York (in his Cheney house of 1928-29). At the time of his death he was just beginning to explore modern architecture in his unrealized Art Deco-inspired Crocker house (1929-39) in Pebble Beach.

Smith’s architectural career lasted only 12 years, from 1919 to 1930. But during these years he (with the assistance of his draftsperson, Lutah Maria Riggs, who joined his office in 1922) produced a remarkable array of buildings, both in quality and quantity–of 80 designs for new or substantially remodeled homes in Santa Barbara County, 54 were built. Many were based on Spanish, Mexican and Hispanic California precedents, but he also designed in the Italian, French Norman, and English Tudor modes. His 1926-28 Crocker Fagan house at Pebble Beach is America’s one and only example of a Byzantine house. In Texas, for the Van Wyck Maverick family (1926-28), he created one of the most impressive courtyard-oriented houses built during these years, and he introduced the world of Spain to, of all places, Fisher’s Island off the coast of New York (in his Cheney house of 1928-29). At the time of his death he was just beginning to explore modern architecture in his unrealized Art Deco-inspired Crocker house (1929-39) in Pebble Beach.

Like many architects of his generation, Smith continually explored and expanded his knowledge of historic as well as contemporary architecture. He visited throughout Mexico making measured drawings and taking photographs, and in the 1920s he returned several times to Europe, examining and recording buildings and gardens in Spain, Italy and France. He amassed an impressive library devoted to architecture and landscape architecture–if one pages through these books one frequently comes across notes indicating individual buildings or details that interested him.

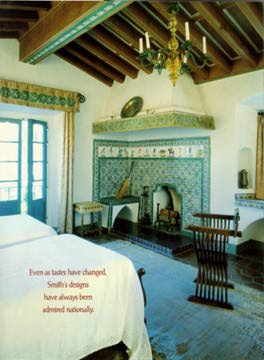

In the 1925 exhibition of the Architectural League of New York, Smith’s work was commended for achieving “an effect that is at once original, personal and distinctly American.” Although taste in architectural imagery has shifted radically in one direction and another from the late 1930s to the present, Smith’s buildings have continued to be discussed and admired on a regional and national level. In recent years architect Charles Moore has written appreciatively about Smith. In his 1990 volume on The Architect and the American Country House, Mark Alan Hewitt wrote that Smith “stood above his peers as a genius whose work epitomized and extended the limits of the Mediterranean idiom.”

A visit today to any one of his houses in Montecito, Pasadena or Woodside will easily reveal why writers and critics have always responded so strongly to his designs. Smith was one of that rare breed of architects who was able to produce buildings that were both subservient to their environment and at the same time able to project strong, beautiful forms into the landscape.